26 Jun What Really Drives Safety

One of the key factors when it comes to embedding a resilient safety culture is having employees who are alert, are vigilant in taking the necessary precautions and are focused on working safely. In short we need people who are switched on. It is a common shared statistic that between 90-95% of all accidents can be attributed to human error. With this as a background it makes sense to have a safety strategy that focuses on getting our workers to be more committed and take responsibility for their safety. We could expect to see a significant progress in our safety records if our personnel would just be more aware of their surroundings, constantly seeking potential hazards, as well as be taking the necessary precautions and action steps to reduce or illuminate risks. While this is true, it is missing a key component. We first have to answer the question, what drives human behaviour?

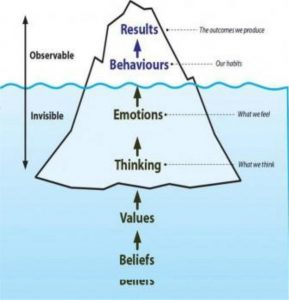

David Rock has popularised the Iceberg metaphor. He explained that the safety culture of a company is the product of the collective set of habits of its workforce. It is understandable that leaders target people’s behaviours in an attempt to see the results they are looking for. Appropriate actions lead to required outcomes. Many behaviour based programmes have this philosophy. Unfortunately, it isn’t that straightforward because our conduct is fueled by our emotions which in turn is driven by our thoughts and beliefs.

David Rock has popularised the Iceberg metaphor. He explained that the safety culture of a company is the product of the collective set of habits of its workforce. It is understandable that leaders target people’s behaviours in an attempt to see the results they are looking for. Appropriate actions lead to required outcomes. Many behaviour based programmes have this philosophy. Unfortunately, it isn’t that straightforward because our conduct is fueled by our emotions which in turn is driven by our thoughts and beliefs.

The focus on results is practical because it is easy to identify and measure. However, the emotions and thinking that influences one’s actions are often downplayed or ignored because they are not so tangible or obvious. Yet, it is these below the surface subtleties that are the true contributors to employee’s work. For leaders to be effective influencers of their team’s functioning it is vital that they to delve below the water to the deeper makeup of their people. Rock summarised, “Our [safety] performance depends upon our behaviour which is guided by our emotions which are triggered when our thoughts (beliefs, habits, memories, assumptions, etc.) interact with certain situations in our daily life.” It is only when we address this dynamic that we will see the dedication towards safety we so earnestly desire.

Let me share a personal story that will drive home the point. Recently I was having dinner with an entrepreneur who was eager to business with me. Getting ready for the evening I was in the men’s bathroom, or so I thought, washing my hands. I was upbeat about the evening as I knew it would be a success. As I was drying my hands a lady walked in. Immediately my whole demeanour changed. Upon seeing her, I went from being bold and confident to being confused. Looking around it became apparent I was in the ladies’ restroom. In another split second my state of mind changed again. This time to total embarrassment as I scurried out of there. In one instant my disposition switched. Instead of walking out with self-assurance I rushed out feeling like I had egg on my face.

What brought about such radical transformation? It was merely a new thought! In essence nothing had changed. The bathroom didn’t change nor did the basin in which I was washing my hands. I was still in the same restaurant certain of a fruitful evening. One moment calm and collected because I believed I was in the comfort of the gents. The realisation that my assumption was wrong drove my urgency to get out of there.

While this is a simple analogy, is it possible that we have ideas concerning safety and performance that are misplaced? The dynamics of changing people’s outlook and commitment towards safety lies in shifting unhelpful hardwired attitudes, perceptions and beliefs. That new thought I had released a completely different set of emotions that triggered another set of behaviours. The challenge leaders face isn’t to control how employees work but to help them embrace a fresh mindset when it comes to safety. Such adjustments in these areas will manifest in the above the water behaviours.

However, before we endeavour in trying to influence our workforce, it is paramount that what we want them to believe is well-defined. It needs to go beyond vague and elusive concepts like zero harm. It has to be more comprehensive than a list of general values hanging on a wall. It is a prerequisite that we first solidify in our own thinking what are the fundamental beliefs required to have a robust safety culture. Do we know precisely what types of attitudes will make a significant difference in daily practices? Then we may want to ask ourselves what is it in our current culture that is preventing this? More importantly, are we willing to address them?

In addition, nothing sets the tone for the safety culture more than the role modelling of its leaders. We will never succeed it persuading our employees if we don’t practice what we preach. What we do speaks far louder than what we say. This is most true when we are pressurised or when things go wrong. It is the decisions, instructions, manner of communicating, and actions in these situations that reveals what our position towards safety is. If at any stage a leader even suggests that safety can or should be neglected; the message is resounding clear – safety isn’t a core value. When a manager quickly excuses the time meant to discuss safety because of the pressing need to get his people into the field, he is sending a strong message that safety isn’t a priority. Likewise, when a supervisor calls his team aside and says, “today we are under immense pressure but let’s take the time to go through the rigorous of today’s tasks to ensure that what we do is done safely.” The message is unmistakable – we don’t compromise on safety. All of these random little nuisances convinces people what the real attitude towards safety is. Over time workers become confident that management is serious about safety. It is not mere lip service. It isn’t long before safety becomes an entrenched culture. Such dedication to safety reinforces the understanding that working safely is a truly celebrated.

In closing, probably the most pertinent questions to ask is what do I believe about safety? How important is it to me personally? What adjustments do I have to make in my own thinking? What unintended messages am I sending? How am I going to intentionally and proactively influence the opinions of my team?

As the Managing Director of the Kinetic Leadership Institute, Dr Brett Solomon, has been involved in numerous safety culture change initiatives with the prestigious mining companies Anglo American, Glencore Alloys, Aveng Moolmans, BHP Billiton and Impala Platinum in South Africa. He has recently been involved in projects with Queensland Aluminium, Sydney Trains and Glencore’s Rolleston coal mine in Australia and currently doing work with Chemanol petrochemical and NOMAC’s power plants in Saudi Arabia as well as the Dominion Diamond’s Ekati Mine in Canada.